This is easily the most common mechanical cause of band failure – and the most easily corrected.

It’s essential that whoever is carrying out band adjustments has been adequately trained and has a good understanding of the mechanisms underlying the gastric band. Adjusting the band is actually every bit as much an art as a science. There are so many factors to take into account and it is certainly not simply a matter of adding or removing fluid.

The most common mistake is to over-fill the band. This is because of an entirely mistaken idea – often on the part of the patient – that ‘more is better’. In other words, if I can lose 1lb a week with 6cc in my band, if I have 8cc I will lose a lot more. This is just wrong – more is not always better!

Moreover, over-tightening of the band has its own risks apart from causing retching, food intolerance and reflux. An over-tight band increases the risk of erosion, pouch dilatation and possibly slippage, all of which may eventually require removal of the device.

Correct adjustment comes back to understanding the mechanism by which the band produces weight loss. The band is NOT designed to prevent food consumption as patients believe: it is not an obstructive device but a satiety device. In other words, it works by creating a sensation of fullness not by preventing eating.

Sometimes the small pouch of stomach above the band can become inflamed, which leads to swelling and mechanical obstruction of the band. This can sometimes be caused by certain types of medication (especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen), but can also be due to stomach bugs, chest infections requiring antibiotics etc. Often the cause is not obvious.

Inflammation of the pouch usually causes reflux and sometimes food intolerance leading to regurgitation. Patients complain that they can’t keep anything down and may become dehydrated due to fluid depletion.

The diagnosis is usually obvious from the history.

Removal of fluid (aspiration) from the band usually results in instantaneous and dramatic improvement. The patient is usually prescribed a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) such as omeprazole and the symptoms usually settle in a few days. The band can then be re-adjusted after a couple of weeks.

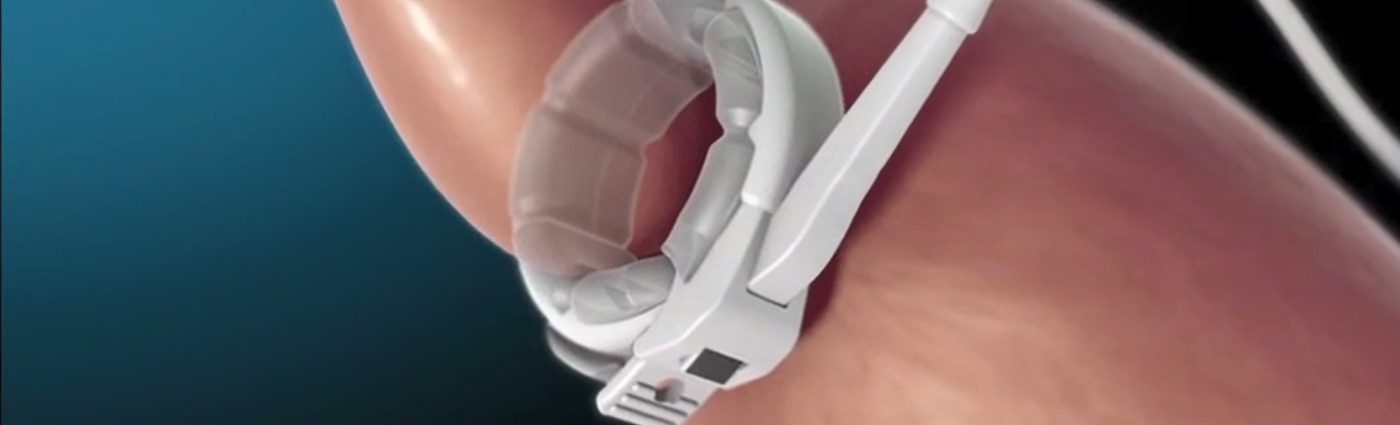

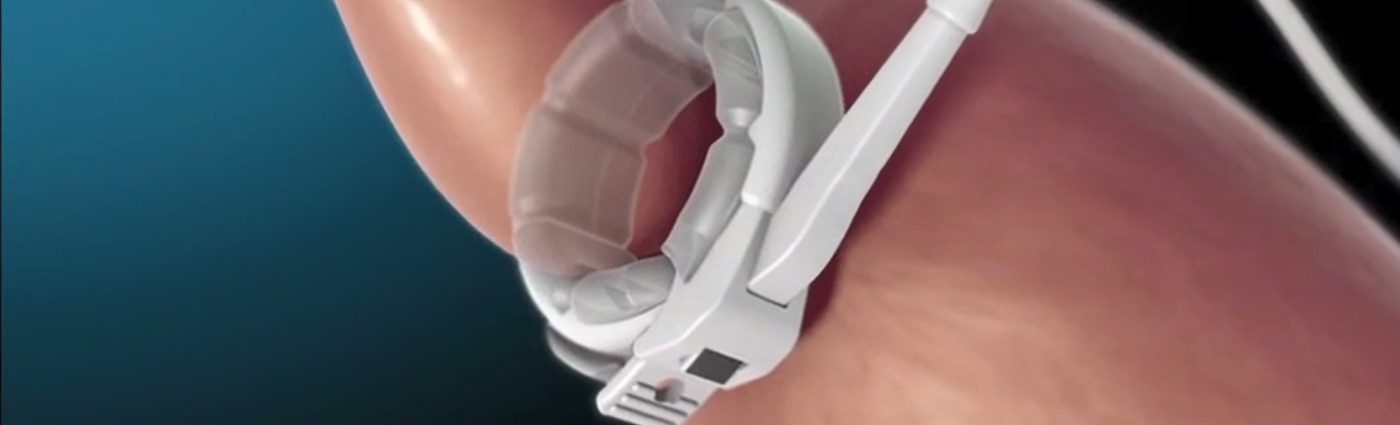

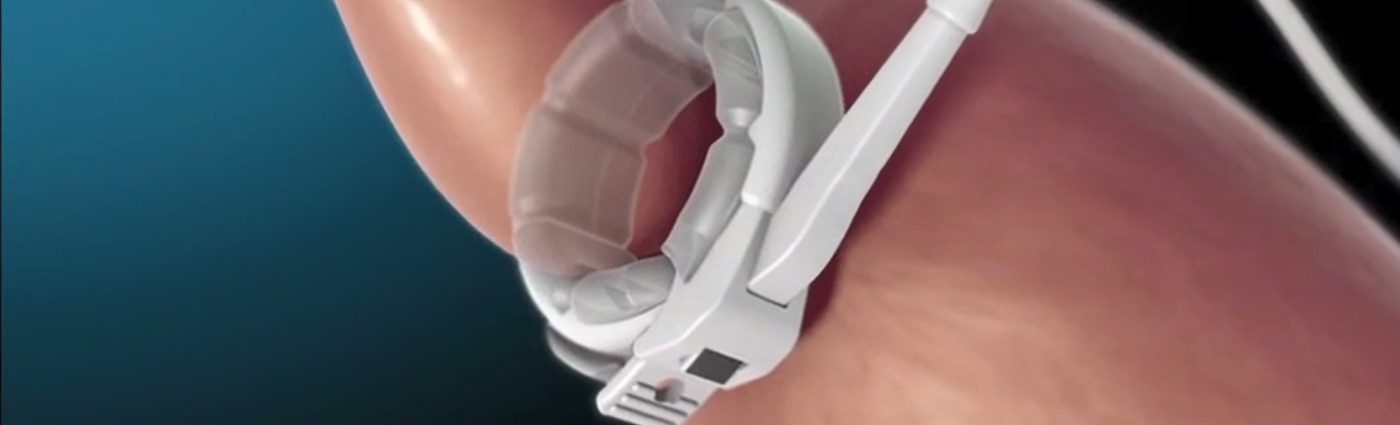

Although it sounds as if the band has slipped off the stomach, this is not the case. In fact what happens is that stomach passes upwards through the band – sometimes called a prolapse. This is shown in the figure opposite.

The amount of stomach above the band may be relatively small, or can be very large. A large slippage always produces symptoms, but a small slippage may remain unnoticed for some time.

The frequency of band slippage varies widely between 1-22% and this probably reflects the experience of the surgeon and the surgical technique used. Our own slippage rate is just 1.4%

There are lots of theories about what causes band slippage, including having a band over-tightened or prolonged vomiting. The most important factor is probably poor surgical technique, but in most cases the precise cause is not obvious.

(NB. The band may be a very safe procedure and it may look simple to perform, but in practice it is anything but simple. It is very easy to make mistakes when implanting a band and even small errors can have a large downstream effect on the patient. In other words, the experience of the surgeon is critical in getting the best from your band).

The usual symptoms of slippage are intolerance of solid foods, regurgitation of food from the pouch, vague upper abdominal discomfort and reflux or heartburn, especially at night.

An X-ray with a barium swallow is the simplest way to confirm the presence of a slippage. This will show the position of the stomach and the size of the prolapse.

A small slippage can sometimes be managed non-surgically. But in most cases surgical revision is needed, though NOT necessarily removal. If the slippage is diagnosed at an early stage and it is not too large, an experienced surgeon can re-position the band without too much difficulty.

Band erosion – also called band migration – is fortunately a rare complication of banding nowadays. In the early days of gastric banding, erosions were quite common (up to 9%), but in most modern bariatric centres the incidence is now very low (just 0.1-0.5%). An erosion is, however, a serious complication of the band, not because it is dangerous per se, but because it always requires removal of the device.

An erosion is exactly what it says – the band actually wears right through the stomach wall, so that if you introduce an endoscope (a special camera) into the stomach, you would be able to see the band. Sometimes, the band becomes infected and this may travel along the band tubing to the access port where it can cause a skin infection or even an abscess. So anyone with a band who has reddening or an obvious infection in the area of the access port, may well have an erosion.

Although it sounds terrible (a ‘hole’ in the stomach) an erosion is not life-threatening.

The cause of erosions is difficult to establish. Some surgeons believe it is due to an infection which happens during surgery, possibly resulting from minor trauma at the time of insertion, or variations in band design. Others believe it may be due to certain classes of drugs, especially anti-inflammatories used in the treatment of arthritis. But it’s important to note that erosion is generally a later complication of banding – usually more than 2-years after surgery. Furthermore, up until the point at which the erosion occurred, many patients were successful with the band.

An erosion can present in lots of ways, sometimes just with a feeling of vague abdominal discomfort. About one-third present with obvious redness/infection in the area of skin over the access port. Patients occasionally say they suddenly felt something “give” in the stomach, which is presumably the point at which band finally broke through the stomach wall. Other clues are that the fluid in the band may be slightly discoloured and there is a sudden need to add a lot more to the band than previously to obtain the same degree of restriction. There may be weight regain for no apparent reason.

The presence of an infection over the access port or sudden lost of restriction from the band, should immediately raise the suspicion of an erosion. A definitive diagnosis is best made endoscopically – a camera is passed through the mouth and into the stomach where the erosion can be seen.

The band needs to be removed. In very experienced hands the band can sometimes be removed via the endoscope if the access port and tubing have already been removed. However, most bands need to be removed surgically and the stomach repaired.

It will usually be necessary to wait for around 3-6-months after removal of the band, before proceeding to any further surgery such as sleeve or gastric bypass. This is because after an erosion there is scarring and some deformity of the stomach wall, which can make further surgery more technically demanding.

Many surgeons believe it would be unwise to implant another band after erosion, because of an increased risk of a further erosion. Not everyone shares this view, however, and the limited scientific evidence is fairly evenly balanced.

My own practice is that if the patient was successful with the first band and she/he is willing to accept the possibility of a slightly increased risk of a second erosion, then implanting another band is perfectly reasonable. Obviously it wouldn’t be sensible to opt for a second band, if the patient had failed with the first!

In a normally functioning gastric band, the volume of the small pouch above the band is about the size of an egg. This limits the amounts of food that can be eaten at any one time and a key behaviour which must be learned by the successful band patient, is to eat small volumes of food and stop as soon as you are no longer hungry.

If, on the other hand, large volumes of food continue to be eaten, then over time the pouch will stretch.

This is especially the case if the band is very tight. This enlargement of the stomach above the band is called pouch dilatation and can occur in up to 10% of patients over time. Risk of pouch enlargement can be greatly increased by an inexperienced surgeon, making the pouch too large during band placement.

Pouch dilatation is a potentially serious complication which may spell the end of the band.

A common finding is that although the band is at its maximum fill-volume, the patient complains of feeling no restriction. This is because the normal mechanism of the band – the satiety (fullness) signal from the pouch to the brain, has been lost due to the stretching of the stomach.

Additional symptoms of pouch enlargement may be indistinguishable from those of a band slippage – food regurgitation, weight gain and nocturnal reflux (heartburn). The two conditions can overlap in that a very large pouch may eventually become a slippage. The difference between the two is that in the case of pouch dilatation alone, the band is in a normal position, whereas in a slippage the stomach has prolapsed upwards through the band.

A barium x-ray will usually show the enlarged pouch (see above).

Initially the treatment is to deflate the band and let the stomach rest, in the belief that the stretched portion will slowly return to normal. In practice, however, it is unlikely that an enlarged pouch will return to normal with restoration of the signalling mechanism.

The other problem, of course, is that when the band is completely empty, the patient will feel no restriction at all and will start to put on weight again.

It is possible to surgically re-position the band, but results are generally disappointing. This is probably because the patient was still unwilling or unable to change behaviour and adhere strictly to much smaller portions. The best plan would be to remove the band and convert to a different procedure – preferably a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. But it must be remembered that pouch enlargement can also occur with gastric bypass, so that if the patient still cannot control portion sizes, the bypass too will fail. And there is no agreed surgical correction for a failed gastric bypass.

The best remedy, of course, it to stick with the band and avoid stretching the pouch in the first place!

Problems with the access port and band tubing are fairly common but, in most cases, not too difficult to correct.

The access port is that part of the band through which adjustments (with 0.9%) saline are performed. At the centre of the port is a dense silicone plug, which is self-sealing provided the correct adjustment needle is used.

The two main problems with the port are leakage and a “flipped” port.

Leakage can occur just because of a slightly awkward needle entry into the access port. It can easily happen and does not mean that whoever did the adjustment was incompetent or careless. It’s usually obvious that there is a leakage in the system, simply because you will notice a marked loss of restriction – you feel hungry, your weight is increasing and you don’t feel the same level of restriction. When you attend the clinic for a routine review, the person performing the adjustment will usually find there is a volume-deficit. In other words, if you were known to have had 6cc in the band at the time of the last adjustment, but you now have 4cc, there is clearly a difference which could only be due to a leak in the system.

It’s usually a good idea to carry out a special x-ray before going ahead with a port-replacement. This is because there is always a chance that the leak may not be coming from the access port, but in the tubing much further up. If the surgeon replaces the port, but that isn’t where the leak is, you are going to be very unhappy!

The surgical procedure to replace the port is simple and normally takes only around 15 minutes, usually under local anaesthetic. A small hole is made in the skin, the port is removed and a new port put in position and connected to the band tubing. This solves the problem in 99% of cases.

In the base of the access port is a steel plate which normally prevents the needle from passing through the port into the tissues. Clearly if the port has flipped over, the metal plate is now the part of the band closest to the skin. This makes it impossible to place the adjustment needle.

In experienced hands, it is sometimes possible to “hook” the access port over into the correct position, but this is not easy and may be uncomfortable for the patient. The safest and easiest option is just to re-position the port and place some strong anchoring sutures to prevent it recurring. This only takes a few minutes and can usually be done under local anaesthetic.

The band tubing which connects the balloon (the part of the band around the stomach) to the access port, is made of silicone and is usually long-lasting and robust. Occasionally, however, the tubing can fracture causing a leak of saline and loss of restriction. The small amount of leaked saline passes into the abdominal cavity and is harmless. Rarely, the band can be perforated during adjustment (see below).

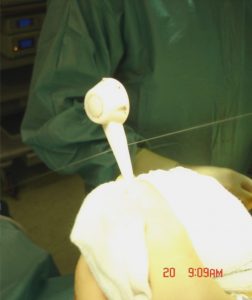

Band accidentally punctured by adjustment needle. At operation the two streams of fluid can be clearly seen leaking from the band. This was easily corrected

A tubing fracture is diagnosed in much the same way as the access port leakage. In other words, there is clearly a loss of volume from the band and the patient has noticed a change in the level of restriction. When you leave the clinic you feel there is definite restriction from the band, but very quickly you notice that the restriction wears off – often within an hour or two as the saline leaks from the band.

However, the clue to it being a tubing problem rather than a leak from the access port, is that in the case of a tubing leak, the fluid removed from the band when the volume is checked, is discoloured. Normal band fluid should be perfectly clear, but in a tubing leak the fluid is usually a brownish colour. Leaks from the access port, however, are usually clear

The way to correct the tubing leak is to put in another port with attached tubing, and join the two sections of tubing using a metal stent. However, if the tubing fracture is high up in the system, it is not always possible to do this. In these cases it is safer to remove the old band and implant a new one.

Infection of the band itself at surgery is a very rare complication – I have only seen two cases in many thousands of bands. It is not known how the infection occurs, but it quickly becomes evident that there is a problem – usually within a week or less. The patient feels very unwell and may have a fever. An MRI scan usually reveals the infected area around the band itself. The treatment is to remove the band immediately and treat the infection with antibiotics.

When the band is implanted, the stomach tissue immediately beneath the band undergoes some changes. It becomes thinner and rather more rigid (fibrotic) than normal tissue. This is a normal finding. Rarely, however, the body seems to react very vigorously to the presence of the band and creates an intense tissue reaction, resulting in marked thickening and constriction of the stomach tissue immediately beneath the band. This thickened, hard and intensely white tissue is called a pseudo-capsule.

This is a problem because the pseudo-capsule acquires a sort of life of its own. It creates a restriction around the upper part of the stomach independently of the band. Sometimes it stabilizes and the patient can manage quite well with the band. However, in other cases the pseudo-capsule progresses and causes problems very like an over-tight band – regurgitation and reflux. Eventually, the band has to be removed and the pseudo-capsule itself has to be surgically removed. Unfortunately, the presence of a pseudo-capsule is an absolute contraindication to any further band surgery.